what amendment is the right to know the witnesses against oneself

The Fifth Subpoena (Amendment V) to the United states Constitution addresses criminal procedure and other aspects of the Constitution. It was ratified, along with ix other manufactures, in 1791 as role of the Nib of Rights. The Fifth Amendment applies to every level of the government, including the federal, state, and local levels, in regard to a U.s.a. denizen or resident of the The states. The Supreme Court furthered the protections of this subpoena through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Subpoena.

1 provision of the Fifth Amendment requires that felonies be tried simply upon indictment past a grand jury. Another provision, the Double Jeopardy Clause, provides the correct of defendants to be tried simply one time in federal courtroom for the same offense. The cocky-incrimination clause provides various protections against cocky-incrimination, including the right of an individual non to serve as a witness in a criminal example in which they are the accused. "Pleading the Fifth" is a colloquial term often used to invoke the self-incrimination clause when witnesses decline to answer questions where the answers might incriminate them. In the 1966 case of Miranda v. Arizona, the Supreme Courtroom held that the self-incrimination clause requires the constabulary to issue a Miranda alert to criminal suspects interrogated while under law custody. The Fifth Amendment also contains the Takings Clause, which allows the federal regime to take private property for public use if the authorities provides "simply compensation."

Like the Fourteenth Amendment, the 5th Amendment includes a due process clause stating that no person shall "be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." The Fifth Amendment's due process clause applies to the federal government, while the Fourteenth Subpoena's due process clause applies to state governments. The Supreme Court has interpreted the Fifth Amendment'south Due Process Clause equally providing two main protections: procedural due process, which requires government officials to follow fair procedures before depriving a person of life, freedom, or belongings, and substantive due process, which protects certain key rights from regime interference. The Supreme Courtroom has too held that the Due Process Clause contains a prohibition against vague laws and an implied equal protection requirement similar to the Fourteenth Amendment'southward Equal Protection Clause.

Text [edit]

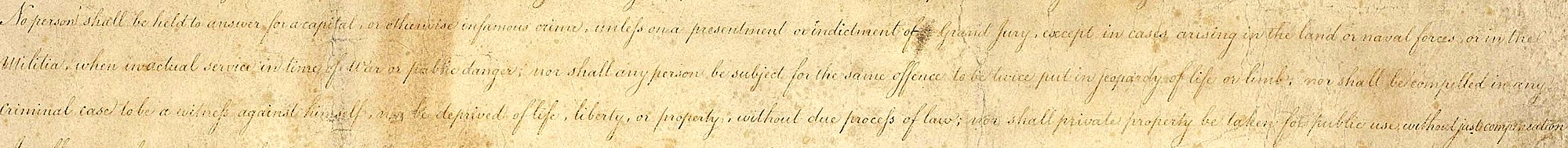

The amendment as proposed by Congress in 1789:

No person shall exist held to respond for a capital, or otherwise infamous offense, unless on a presentment or indictment of a M Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in bodily service in time of War or public danger; nor shall whatsoever person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall exist compelled in any criminal instance to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due procedure of law; nor shall individual property be taken for public utilise, without just compensation.

The hand-written copy of the proposed Nib of Rights, 1789, cropped to show just the text that would later on exist ratified as the Fifth Amendment

Background before adoption [edit]

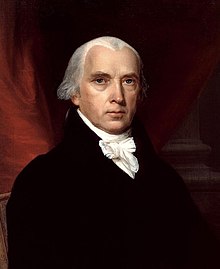

On June 8, 1789, Congressman James Madison introduced several proposed constitutional amendments during a speech to the House of Representatives.[1] His draft linguistic communication that later became the 5th Amendment was equally follows:[1] [2]

No person shall exist subject, except in cases of impeachment, to more one punishment or trial for the same law-breaking; nor shall be compelled to exist a witness confronting himself; nor exist deprived of life, liberty, or holding, without due procedure of constabulary; nor be obliged to relinquish his property, where it may be necessary for public use, without only compensation....[Due east]xcept in cases of impeachments, and cases arising in the land or naval forces, or the militia when on actual service, in time of war or public danger... in all crimes punishable with loss of life or member, presentment or indictment past a grand jury shall be an essential preliminary...

This draft was edited by Congress; all the material before the start ellipsis was placed at the end, and some of the wording was modified. After approval by Congress, the amendment was ratified by the states on December 15, 1791 equally part of the Bill of Rights. Every ane of the five clauses in the final amendment appeared in Madison'due south draft, and in their last club those clauses are the Grand Jury Clause (which Madison had placed last), the Double Jeopardy Clause, the Self Incrimination Clause, the Due Process Clause, and and then the Takings Clause.

Grand jury [edit]

The thousand jury is a pre-constitutional common police force institution, and a constitutional fixture in its own right exclusively embracing common constabulary. The process applies to the states to the extent that the states take incorporated thousand juries and/or common law. Most states take an alternative civil process. "Although country systems of criminal procedure differ greatly amid themselves, the grand jury is similarly guaranteed by many state constitutions and plays an important role in fair and effective police force enforcement in the overwhelming [p688] bulk of united states." Branzburg v. Hayes (No. lxx-85) 1972. Grand juries, which return indictments in many criminal cases, are composed of a jury of peers and operate in airtight deliberation proceedings; they are given specific instructions regarding the constabulary by the approximate. Many constitutional restrictions that apply in court or in other situations practise non apply during thou jury proceedings. For case, the exclusionary dominion does non utilize to certain evidence presented to a grand jury; the exclusionary rule states that evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth, Fifth or Sixth amendments cannot exist introduced in court.[3] As well, an individual does non take the right to have an chaser nowadays in the grand jury room during hearings. An individual would take such a right during questioning past the constabulary while in custody, but an individual testifying before a g jury is free to leave the m jury room to consult with his chaser outside the room before returning to reply a question.

Currently, federal constabulary permits the trial of misdemeanors without indictments.[iv] Additionally, in trials of non-capital felonies, the prosecution may proceed without indictments if the defendants waive their Fifth Amendment right.

Grand jury indictments may exist amended by the prosecution only in express circumstances. In Ex Parte Bain, 121 U.S. ane (1887), the Supreme Court held that the indictment could not be changed at all by the prosecution. United States v. Miller, 471 U.S. 130 (1985) partly reversed Ex parte Bain; now, an indictment'due south scope may be narrowed by the prosecution. Thus, lesser included charges may be dropped, but new charges may not exist added.

The Grand Jury Clause of the Fifth Subpoena does not protect those serving in the armed forces, whether during wartime or peacetime. Members of the state militia called up to serve with federal forces are not protected under the clause either. In O'Callahan v. Parker, 395 U.S. 258 (1969), the Supreme Court held that only charges relating to service may be brought against members of the militia without indictments. As a conclusion, O'Callahan, however, lived for a limited duration and was more a reflection of Justice William O. Douglas's distrust of presidential ability and anger at the Vietnam Conflict.[5] O'Callahan was overturned in 1987, when the Court held that members of the militia in actual service may be tried for whatever offense without indictments.[six]

The grand jury indictment clause of the 5th Amendment has not been incorporated under the Fourteenth Amendment.[7] This means the 1000 jury requirement applies only to felony charges in the federal court system. While many states practice employ m juries, no defendant has a Fifth Amendment correct to a grand jury for criminal charges in state court. States are gratuitous to abolish g juries, and many (though not all) take replaced them with preliminary hearing.

Infamous criminal offense [edit]

Whether a crime is "infamous", for purposes of the Grand Jury Clause, is adamant past the nature of the punishment that may be imposed, non the penalty that is actually imposed;[8] however, crimes punishable past expiry must be tried upon indictments. The historical origin of "infamous crime" comes from the infamia, a penalization nether Roman law by which a citizen was deprived of his citizenship.[9] [x] In United states v. Moreland, 258 U.South. 433 (1922), the Supreme Courtroom held that incarceration in a prison house or penitentiary, as opposed to a correction or reformation house, attaches infamy to a criminal offence. In Mackin v. United States, 117 U.S. 348 (1886), the Supreme Court judged that "'Infamous crimes' are thus, in the virtually explicit words, defined to be those 'punishable by imprisonment in the penitentiary'," while it later in Green v. United States 356 U.S. 165 (1957) stated that "imprisonment in a penitentiary can be imposed only if a law-breaking is subject to imprisonment exceeding i year." Therefore, an infamous criminal offense is i that is punished past imprisonment for over one year. Susan Brown, a former defence force attorney and Professor of Law at the University of Dayton School of Police, concluded: "Since this is essentially the definition of a felony, infamous crimes interpret as felonies."[eleven]

Double jeopardy [edit]

- ... nor shall any person exist subject for the same criminal offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb...[12]

The Double Jeopardy Clause encompasses four distinct prohibitions: subsequent prosecution later amortization, subsequent prosecution after confidence, subsequent prosecution later on sure mistrials, and multiple punishment in the aforementioned indictment.[13] Jeopardy applies when the jury is empaneled in a jury trial, when the first witness is sworn in during a bench trial, or when a plea is rendered.[xiv]

Prosecution after acquittal [edit]

The government is not permitted to appeal or try again subsequently the entry of an amortization, whether a directed verdict before the case is submitted to the jury,[15] a directed verdict after a deadlocked jury,[xvi] an appellate reversal for sufficiency (except past direct appeal to a college appellate court),[17] or an "implied acquittal" via conviction of a bottom included offense.[18] In add-on, the government is barred by collateral estoppel from re-litigating against the same defense, a fact necessarily institute past the jury in a prior acquittal,[xix] even if the jury hung on other counts.[20]

This principle does not prevent the government from appealing a pre-trial movement to dismiss[21] or other not-merits dismissal,[22] or a directed verdict after a jury conviction,[23] nor does it prevent the trial guess from entertaining a movement for reconsideration of a directed verdict, if the jurisdiction has so provided by rule or statute.[24] Nor does information technology prevent the government from retrying the accused after an appellate reversal other than for sufficiency,[25] including habeas,[26] or "thirteenth juror" appellate reversals notwithstanding sufficiency[27] on the principle that jeopardy has not "terminated." There is also an exception for judicial blackmail in a demote trial.[28]

Multiple penalisation, including prosecution after conviction [edit]

In Blockburger five. Us (1932), the Supreme Court announced the post-obit test: the authorities may separately effort to punish the accused for two crimes if each crime contains an element that the other does not.[29] Blockburger is the default rule, unless the legislature intends to depart; for instance, Continuing Criminal Enterprise (CCE) may be punished separately from its predicates,[thirty] as can conspiracy.[31]

The Blockburger examination, originally developed in the multiple punishments context, is also the test for prosecution after conviction.[32] In Grady v. Corbin (1990), the Court held that a double jeopardy violation could lie even where the Blockburger test was not satisfied,[33] but Grady was overruled in United States 5. Dixon (1993).[34]

Prosecution afterwards mistrial [edit]

The rule for mistrials depends upon who sought the mistrial. If the accused moves for a mistrial, there is no bar to retrial, unless the prosecutor acted in "bad faith", i.eastward., goaded the defendant into moving for a mistrial because the government specifically wanted a mistrial.[35] If the prosecutor moves for a mistrial, there is no bar to retrial if the trial judge finds "manifest necessity" for granting the mistrial.[36] The aforementioned standard governs mistrials granted sua sponte.

Prosecution in different states [edit]

In Heath 5. Alabama (1985), the Supreme Court held, that the Fifth Amendment dominion against double jeopardy does not prohibit 2 dissimilar states from separately prosecuting and convicting the aforementioned individual for the same illegal act.

Self-incrimination [edit]

The 5th Amendment protects individuals from being forced to incriminate themselves. Incriminating oneself is divers every bit exposing oneself (or some other person) to "an accusation or accuse of crime," or every bit involving oneself (or another person) "in a criminal prosecution or the danger thereof."[37] The privilege against compelled self-incrimination is defined every bit "the constitutional right of a person to pass up to answer questions or otherwise give testimony against himself".[38] To "plead the 5th" is to refuse to answer whatever question because "the implications of the question, in the setting in which it is asked" atomic number 82 a claimant to possess a "reasonable cause to apprehend danger from a directly answer", believing that "a responsive answer to the question or an explanation of why it cannot exist answered might exist dangerous because injurious disclosure could result."[39]

Historically, the legal protection against compelled self-incrimination was directly related to the question of torture for extracting data and confessions.[40] [41]

The legal shift away from widespread utilize of torture and forced confession dates to turmoil of the late 16th and early 17th century in England.[42]

The Supreme Court of the U.s. has held that "a witness may accept a reasonable fearfulness of prosecution and yet be innocent of any wrongdoing. The privilege serves to protect the innocent who otherwise might be ensnared by ambiguous circumstances."[43]

However, Professor James Duane of the Regent University School of Law argues that the Supreme Court, in a five–4 decision in Salinas v. Texas,[44] significantly weakened the privilege, saying "our choice to use the Fifth Amendment privilege can be used against you lot at trial depending exactly how and where you do it."[45]

In the Salinas case, justices Alito, Roberts, and Kennedy held that "the Fifth Amendment's privilege confronting cocky-incrimination does not extend to defendants who simply decide to remain mute during questioning. Long-standing judicial precedent has held that whatsoever witness who desires protection against self-incrimination must explicitly claim that protection."

Justice Thomas, siding with Alito, Roberts and Kennedy, in a separate opinion, held that, "Salinas' Fifth Amendment privilege would not have been applicable even if invoked because the prosecutor'southward testimony regarding his silence did not compel Salinas to requite self-incriminating testimony." Justice Antonin Scalia joined Thomas' opinion.[46]

Legal proceedings and congressional hearings [edit]

The Fifth Amendment privilege confronting compulsory cocky-incrimination applies when an individual is called to evidence in a legal proceeding.[47] The Supreme Court ruled that the privilege applies whether the witness is in a federal courtroom or, under the incorporation doctrine of the Fourteenth Amendment, in a state court,[48] and whether the proceeding itself is criminal or civil.[49]

The correct to remain silent was asserted at grand jury or congressional hearings in the 1950s, when witnesses testifying before the House Committee on United nations-American Activities or the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee claimed the right in response to questions concerning their alleged membership in the Communist Party. Under the Blood-red Scare hysteria at the fourth dimension of McCarthyism, witnesses who refused to answer the questions were accused as "5th amendment communists". They lost jobs or positions in unions and other political organizations, and suffered other repercussions subsequently "taking the Fifth."

Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) asked, "Are you at present, or have yous always been, a member of the Communist Party?" while he was chairman of the Senate Regime Operations Committee Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Albeit to a previous Communist Party membership was not sufficient. Witnesses were besides required to "proper name names", i.east. implicate others they knew to be Communists or who had been Communists in the past. Academy Accolade winning director Elia Kazan testified earlier the House Committee on Un-American Activities that he had belonged to the Communist Party briefly in his youth. He as well "named names", which incurred enmity of many in Hollywood. Other entertainers such every bit Zippo Mostel found themselves on a Hollywood blacklist after taking the Fifth, and were unable to find piece of work for a while in bear witness business. Pleading the Fifth in response to such questions was held inapplicable,[ citation needed ] since existence a Communist itself was non a criminal offence.

The amendment has also been used by defendants and witnesses in criminal cases involving the American Mafia.[ citation needed ]

Statements fabricated to non-governmental entities [edit]

The privilege against cocky-incrimination does non protect an individual from beingness suspended from membership in a non-governmental, self-regulatory organisation (SRO), such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), where the individual refuses to answer questions posed by the SRO. An SRO itself is non a courtroom of law, and cannot ship a person to jail. SROs, such as the NYSE and the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), are generally not considered to be state actors. See U.s. v. Solomon,[50] D. Fifty. Cromwell Invs., Inc. v. NASD Regulation, Inc.,[51] and Marchiano v. NASD.[52] SROs too lack subpoena powers. They rely heavily on requiring testimony from individuals past wielding the threat of loss of membership or a bar from the industry (permanent, if decided by the NASD) when the private asserts his Fifth Amendment privilege against compelled self-incrimination. If a person chooses to provide statements in testimony to the SRO, the SRO may provide information near those statements to law enforcement agencies, who may and then use the statements in a prosecution of the private.

Custodial interrogation [edit]

The Fifth Amendment limits the use of evidence obtained illegally by law enforcement officers. Originally, at common law, even a confession obtained past torture was admissible. However, past the eighteenth century, common constabulary in England provided that coerced confessions were inadmissible. The mutual constabulary rule was incorporated into American police force past the courts. The Supreme Court has repeatedly overruled convictions based on such confessions, in cases such every bit Brown five. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1936).

Law enforcement responded by switching to more subtle techniques, but the courts held that such techniques, even if they do not involve physical torture, may render a confession involuntary and inadmissible. In Chambers 5. Florida (1940) the Court held a confession obtained subsequently five days of prolonged questioning, during which fourth dimension the defendant was held incommunicado, to be coerced. In Ashcraft v. Tennessee (1944), the doubtable had been interrogated continuously for thirty-six hours under electric lights. In Haynes five. Washington,[53] the Court held that an "unfair and inherently coercive context" including a prolonged interrogation rendered a confession inadmissible.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966) was a landmark case involving confessions. Ernesto Miranda had signed a statement confessing to the crime, but the Supreme Court held that the confession was inadmissible considering the defendant had not been advised of his rights. The Court held "the prosecution may non use statements ... stemming from custodial interrogation of the defendant unless it demonstrates the utilize of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination." Custodial interrogation is initiated past law enforcement after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of movement before being questioned as to the specifics of the crime. As for the procedural safeguards to be employed, unless other fully effective means are devised to inform accused persons of their right of silence and to assure a continuous opportunity to practice it, the post-obit measures are required. Before whatever questioning, the person must be warned that he has a right to remain silent, that any argument he does make may be used as evidence against him, and that he has a correct to the presence of an attorney, either retained or appointed.

The warning Master Justice Earl Warren referred to is now called the Miranda alarm, and it is customarily delivered by the police to an individual before questioning. Miranda has been clarified by several further Supreme Court rulings. For the warning to be necessary, the questioning must be conducted under "custodial" circumstances. A person detained in jail or under abort is, of grade, deemed to be in police custody. Alternatively, a person who is under the reasonable conventionalities that he may non freely leave from the restraint of police force enforcement is also deemed to be in "custody." That conclusion of "reasonableness" is based on a totality of the objective circumstances. A mere presence at a police station may not exist sufficient, but neither is such a presence required. Traffic stops are not deemed custodial. The Courtroom has ruled that age can exist an objective cistron. In Yarborough v. Alvarado (2004), the Court held that "a country-court decision that failed to mention a 17-twelvemonth-erstwhile'south historic period as part of the Miranda custody assay was not objectively unreasonable".[54] In her concurring stance Justice O'Connor wrote that a suspect'due south historic period may indeed "exist relevant to the 'custody' inquiry";[55] the Courtroom did not discover it relevant in the specific case of Alvarado. The Court affirmed that historic period could exist a relevant and objective factor in J.D.B. v. North Carolina where they ruled that "and so long as the child's age was known to the officer at the time of law questioning, or would accept been objectively apparent to a reasonable officer, its inclusion in the custody analysis is consistent with the objective nature of that test".[54]

The questioning does not accept to be explicit to trigger Miranda rights. For example, two police officers engaging in a chat designed to elicit an incriminating statement from a suspect would constitute questioning. A person may cull to waive his Miranda rights, but the prosecution has the burden of showing that such a waiver was really made.

A confession non preceded by a Miranda warning where i was necessary cannot be admitted every bit bear witness confronting the confessing party in a judicial proceeding. The Supreme Court, however, has held that if a defendant voluntarily testifies at the trial that he did not commit the crime, his confession may exist introduced to challenge his brownie, to "impeach" the witness, even if information technology had been obtained without the warning.

In Hiibel v. 6th Judicial Commune Courtroom of Nevada (2004), the Supreme Court ruled 5–4 that being required to place oneself to police nether states' terminate and identify statutes is not an unreasonable search or seizure, and is not necessarily self-incrimination.

Explicit invocation [edit]

In June 2010, the Supreme Court ruled in Berghuis five. Thompkins that a criminal suspect must at present invoke the right to remain silent unambiguously.[56] Unless and until the suspect actually states that he is relying on that right, police may go along to interact with (or question) him, and any voluntary statement he makes can be used in court. The mere act of remaining silent is, on its own, bereft to imply the suspect has invoked those rights. Furthermore, a voluntary reply, even afterwards lengthy silence, tin can be construed as implying a waiver. The new rule volition defer to police in cases where the suspect fails to assert the right to remain silent. This standard was extended in Salinas v. Texas in 2013 to cases where individuals non in custody who volunteer to answer officers' questions and who are not told their Miranda rights. The Court stated that there was no "ritualistic formula" necessary to affirm this right, but that a person could not practice so "by simply standing mute."[57] [58]

Production of documents [edit]

Nether the Act of Production Doctrine, the act of an individual in producing documents or materials (e.thousand., in response to a subpoena) may have a "testimonial aspect" for purposes of the individual's right to assert the 5th Amendment right confronting cocky-incrimination to the extent that the private'due south act of production provides information not already in the hands of law enforcement personnel virtually the (ane) existence; (ii) custody; or (iii) authenticity, of the documents or materials produced. See United States five. Hubbell. In Boyd v. United States,[59] the U.S. Supreme Court stated that "Information technology is equivalent to a compulsory production of papers to make the nonproduction of them a confession of the allegations which it is pretended they will prove".

By corporations [edit]

Corporations may as well be compelled to maintain and turn over records; the Supreme Court has held that the Fifth Amendment protections confronting self-incrimination extend only to "natural persons".[sixty] The Court has besides held that a corporation'southward custodian of records can exist forced to produce corporate documents even if the act of product would incriminate him personally.[61] The only limitation on this rule is that the jury cannot exist told that the custodian personally produced those documents in any subsequent prosecution of him, merely the jury is all the same allowed to describe adverse inferences from the content of the documents combined with the position of the custodian in the corporation.

Refusal to evidence in a criminal case [edit]

In Griffin v. California (1965), the Supreme Court ruled that a prosecutor may non ask the jury to draw an inference of guilt from a defendant'due south refusal to testify in his ain defense. The Court overturned as unconstitutional nether the federal constitution a provision of the California land constitution that explicitly granted such power to prosecutors.[62]

Refusal to testify in a ceremonious case [edit]

While defendants are entitled to assert the right against compelled self-incrimination in a civil court example, at that place are consequences to the assertion of the right in such an action.

The Supreme Court has held that "the Fifth Amendment does not forbid adverse inferences confronting parties to civil actions when they refuse to show in response to probative evidence offered against them." Baxter five. Palmigiano,[63] "[A]s Mr. Justice Brandeis alleged, speaking for a unanimous courtroom in the Tod case, 'Silence is often evidence of the most persuasive character.'"[64] "'Failure to contest an assertion ... is considered evidence of amenability ... if it would have been natural under the circumstances to object to the assertion in question.'"[65]

In Baxter, the state was entitled to an adverse inference against Palmigiano considering of the evidence against him and his exclamation of the Fifth Amendment correct.

Some ceremonious cases are considered "criminal cases" for the purposes of the Fifth Amendment. In Boyd v. Usa, the U.S. Supreme Courtroom stated that "A proceeding to forfeit a person's appurtenances for an offence against the laws, though civil in form, and whether in rem or in personam, is a "criminal instance" inside the significant of that office of the Fifth Amendment which declares that no person "shall be compelled, in whatever criminal instance, to be a witness against himself."[66]

In United States v. Lileikis, the court ruled that Aleksandras Lileikis was not entitled to Fifth Amendment protections in a civil denaturalization case fifty-fifty though he faced criminal prosecution in Lithuania, the country that he would exist deported to if denaturalized.[67]

Federal income tax [edit]

In some cases, individuals may be legally required to file reports that call for information that may exist used against them in criminal cases. In United states 5. Sullivan,[68] the United states Supreme Court ruled that a taxpayer could not invoke the Fifth Amendment's protections as the ground for refusing to file a required federal income tax return. The Courtroom stated: "If the form of return provided called for answers that the accused was protected from making[,] he could have raised the objection in the return, but could not on that account refuse to make whatsoever return at all. Nosotros are not called on to decide what, if annihilation, he might accept withheld."[69]

In Garner v. United states,[70] the accused was bedevilled of crimes involving a conspiracy to "set" sporting contests and to transmit illegal bets. During the trial the prosecutor introduced, as evidence, the taxpayer'south federal income tax returns for various years. In one render the taxpayer had showed his occupation to be "professional gambler." In various returns the taxpayer had reported income from "gambling" or "wagering." The prosecution used this to aid contradict the taxpayer's argument that his interest was innocent. The taxpayer tried unsuccessfully to keep the prosecutor from introducing the tax returns as show, arguing that since the taxpayer was legally required to report the illegal income on the returns, he was being compelled to be a witness confronting himself. The Supreme Court agreed that he was legally required to report the illegal income on the returns, but ruled that the right confronting self-incrimination still did non utilise. The Court stated that "if a witness nether coercion to testify makes disclosures instead of claiming the right, the Government has not 'compelled' him to incriminate himself."[71]

Sullivan and Garner are viewed as continuing, in tandem, for the proposition that on a required federal income tax return a taxpayer would probably have to report the amount of the illegal income, merely might validly merits the right by labeling the item "Fifth Amendment" (instead of "illegal gambling income," "illegal drug sales," etc.)[72] The United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit has stated: "Although the source of income might exist privileged, the amount must be reported."[73] The U.South. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Excursion has stated: "...the amount of a taxpayer'due south income is not privileged even though the source of income may be, and 5th Amendment rights can exist exercised in compliance with the taxation laws 'by simply listing his alleged ill-gotten gains in the space provided for "miscellaneous" income on his taxation form'."[74] In another case, the Courtroom of Appeals for the 5th Circuit stated: "While the source of some of [the defendant] Johnson's income may have been privileged, bold that the jury believed his uncorroborated testimony that he had illegal dealings in gold in 1970 and 1971, the corporeality of his income was not privileged and he was required to pay taxes on it."[75] In 1979, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit stated: "A careful reading of Sullivan and Garner, therefore, is that the self-incrimination privilege can be employed to protect the taxpayer from revealing the data as to an illegal source of income, merely does not protect him from disclosing the amount of his income."[76]

Grants of amnesty [edit]

If the government gives an individual immunity, then that individual may exist compelled to testify. Immunity may be "transactional immunity" or "use immunity"; in the former, the witness is immune from prosecution for offenses related to the testimony; in the latter, the witness may be prosecuted, but his testimony may not be used against him. In Kastigar v. United States,[77] the Supreme Courtroom held that the regime need only grant use immunity to compel testimony. The utilise amnesty, however, must extend not only to the testimony made by the witness, just also to all evidence derived therefrom. This scenario nigh normally arises in cases related to organized crime.

Tape keeping [edit]

A statutorily required record-keeping system may go too far such that it implicates a record-keeper'southward right against self-incrimination. A three part examination laid out by Albertson v. Destructive Activities Control Lath,[78] is used to determine this: 1. the law targets a highly selective group inherently suspect of criminal activities; 2. the activities sought to be regulated are already permeated with criminal statutes as opposed to essentially being non-criminal and largely regulatory; and 3. the disclosure compelled creates a likelihood of prosecution and is used against the record-keeper. In this case, the Supreme Courtroom struck down an order past the Subversive Activities Control Board requiring members of the Communist Political party to register with the authorities and upheld an assertion of the privilege against cocky-incrimination, on the grounds that statute under which the order had been issued was "directed at a highly selective group inherently doubtable of criminal activities."

In Leary v. United States,[79] the courtroom struck downwardly the Marijuana Tax Human activity considering its record keeping statute required self-incrimination.

In Haynes v. United States,[fourscore] the Supreme Court ruled that, because bedevilled felons are prohibited from owning firearms, requiring felons to register whatever firearms they owned constituted a form of self-incrimination and was therefore unconstitutional.

Combinations & passwords [edit]

While no such case has yet arisen, the Supreme Court has indicated that a respondent cannot be compelled to plough over "the contents of his own mind", eastward.thou. the password to a bank business relationship (doing so would prove his command of it).[81] [82] [83]

Lower courts have given conflicting decisions on whether forced disclosure of computer passwords is a violation of the Fifth Amendment.

In In re Boucher (2009), the US District Courtroom of Vermont ruled that the 5th Amendment might protect a defendant from having to reveal an encryption countersign, or even the existence of one, if the production of that password could be deemed a self-incriminating "act" under the 5th Subpoena. In Boucher, production of the unencrypted bulldoze was accounted not to be a cocky-incriminating act, as the authorities already had sufficient evidence to necktie the encrypted data to the defendant.[84]

In Jan 2012 a federal judge in Denver ruled that a banking company-fraud doubtable was required to give an unencrypted copy of a laptop difficult drive to prosecutors.[85] [86] However, in February 2012 the Eleventh Circuit ruled otherwise—finding that requiring a defendant to produce an encrypted drive'due south password would violate the Constitution, condign the starting time federal circuit courtroom to rule on the issue.[87] [88] In April 2013, a District Court magistrate estimate in Wisconsin refused to compel a doubtable to provide the encryption password to his hard drive later on FBI agents had unsuccessfully spent months trying to decrypt the data.[89] [90] The Oregon Supreme Courtroom ruled that unlocking a phone with a passcode is testimonial under Commodity I, section 12 of the state constitution, thus compelling it would exist unconstitutional. Its ruling unsaid, however, that unlocking via biometrics may be allowed.[91]

Employer coercion [edit]

As a condition of employment, workers may be required to answer their employer's narrowly defined questions regarding behave on the job. If an employee invokes the Garrity rule (sometimes called the Garrity Warning or Garrity Rights) before answering the questions, then the answers cannot be used in criminal prosecution of the employee.[92] This principle was developed in Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.Southward. 493 (1967). The rule is most commonly practical to public employees such as police officers.

Due process [edit]

The Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution each contain a due process clause. Due process deals with the administration of justice and thus the due process clause acts as a safeguard from capricious deprival of life, liberty, or property by the authorities outside the sanction of law.[93] [94] [95] The Supreme Court has interpreted the due procedure clauses to provide four protections: procedural due procedure (in civil and criminal proceedings), substantive due process, a prohibition against vague laws, and every bit the vehicle for the incorporation of the Neb of Rights.

Takings Clause [edit]

Eminent domain [edit]

The "Takings Clause", the last clause of the Fifth Amendment, limits the power of eminent domain by requiring "just compensation" exist paid if private property is taken for public use. This provision of the Fifth Amendment originally applied but to the federal government, merely the U.S. Supreme Courtroom ruled in the 1897 case Chicago, B. & Q. Railroad Co. v. Chicago that the Fourteenth Amendment incidentally extended the effects of that provision to united states. The federal courts, however, take shown much deference to the determinations of Congress, and fifty-fifty more and then to the determinations of the country legislatures, of what constitutes "public utilise". The property demand not actually be used by the public; rather, information technology must be used or disposed of in such a manner as to do good the public welfare or public interest. One exception that restrains the federal government is that the property must be used in practise of a authorities's enumerated powers.

The owner of the property that is taken by the government must be justly compensated. When determining the amount that must be paid, the regime does not need to take into account any speculative schemes in which the owner claims the property was intended to exist used. Usually, the fair market value of the property determines "merely bounty". If the property is taken earlier the payment is made, involvement accrues (though the courts have refrained from using the term "interest").

Property nether the Fifth Amendment includes contractual rights stemming from contracts between the United states of america, a U.Southward. land or any of its subdivisions and the other contract partner(south), because contractual rights are property rights for purposes of the Fifth Amendment.[96] The U.s. Supreme Court held in Lynch v. Us, 292 U.S. 571 (1934) that valid contracts of the Us are property, and the rights of individual individuals arising out of them are protected by the 5th Amendment. The court said: "The Fifth Amendment commands that holding be not taken without making just compensation. Valid contracts are belongings, whether the obligor be a private private, a municipality, a country, or the United States. Rights against the United States arising out of a contract with it are protected past the Fifth Amendment. Usa v. Fundamental Pacific R. Co., 118 U. South. 235, 118 U. Southward. 238; U.s.a. v. Northern Pacific Ry. Co., 256 U. South. 51, 256 U. Southward. 64, 256 U. South. 67. When the U.s. enters into contract relations, its rights and duties therein are governed generally by the law applicative to contracts between individual individuals."[97]

The federal courts take non restrained country and local governments from seizing privately owned land for private commercial evolution on behalf of private developers. This was upheld on June 23, 2005, when the Supreme Court issued its stance in Kelo v. City of New London. This v–4 determination remains controversial. The majority opinion, by Justice Stevens, found that it was appropriate to defer to the city's decision that the development plan had a public purpose, saying that "the city has carefully formulated a development plan that it believes will provide observable benefits to the community, including, merely not express to, new jobs and increased tax acquirement." Justice Kennedy'due south concurring opinion observed that in this item example the development programme was not "of chief do good to ... the developer" and that if that was the case the plan might have been impermissible. In the dissent, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor argued that this conclusion would permit the rich to benefit at the expense of the poor, asserting that "Any property may now exist taken for the benefit of another private party, simply the fallout from this decision volition non be random. The beneficiaries are probable to be those citizens with asymmetric influence and power in the political process, including large corporations and development firms." She argued that the determination eliminates "whatsoever distinction between private and public employ of property—and thereby effectively delete[s] the words 'for public apply' from the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment". A number of states, in response to Kelo, have passed laws and/or state ramble amendments which make information technology more difficult for state governments to seize private land. Takings that are non "for public use" are non directly covered by the doctrine,[98] however such a taking might violate due procedure rights under the Fourteenth amendment, or other applicable law.

The exercise of the law ability of the country resulting in a taking of private property was long held to be an exception to the requirement of authorities paying but compensation. However the growing tendency under the various state constitution's taking clauses is to compensate innocent third parties whose property was destroyed or "taken" equally a result of police force action.[99]

Just compensation [edit]

The last 2 words of the amendment promise "simply compensation" for takings by the authorities. In Us five. 50 Acres of Land (1984), the Supreme Courtroom wrote that "The Court has repeatedly held that but compensation normally is to be measured by "the marketplace value of the belongings at the time of the taking contemporaneously paid in money." Olson v. United States, 292 U.S. 246 (1934) ... Deviation from this mensurate of just compensation has been required simply "when marketplace value has been as well difficult to find, or when its awarding would result in manifest injustice to owner or public". U.s. v. Commodities Trading Corp., 339 U.South. 121, 123 (1950).

Civil asset forfeiture [edit]

Civil asset forfeiture[100] or occasionally civil seizure, is a controversial legal procedure in which law enforcement officers have avails from persons suspected of involvement with crime or illegal activeness without necessarily charging the owners with wrongdoing. While ceremonious procedure, every bit opposed to criminal procedure, generally involves a dispute between 2 private citizens, civil forfeiture involves a dispute betwixt constabulary enforcement and property such as a pile of greenbacks or a house or a boat, such that the matter is suspected of being involved in a law-breaking. To get dorsum the seized property, owners must prove it was not involved in criminal activity. Sometimes it can mean a threat to seize belongings also every bit the act of seizure itself.[101]

In ceremonious forfeiture, assets are seized by police based on a suspicion of wrongdoing, and without having to accuse a person with specific wrongdoing, with the case being between police and the thing itself, sometimes referred to by the Latin term in rem, significant "against the property"; the holding itself is the accused and no criminal charge against the owner is needed.[100] If holding is seized in a ceremonious forfeiture, it is "up to the owner to bear witness that his greenbacks is make clean"[102] and the court can counterbalance a accused'south apply of their 5th amendment right to remain silent in their decision.[103] In civil forfeiture, the test in most cases[104] is whether police feel at that place is a preponderance of the evidence suggesting wrongdoing; in criminal forfeiture, the examination is whether police force feel the bear witness is beyond a reasonable doubt, which is a tougher test to meet.[102] [105] In contrast, criminal forfeiture is a legal activeness brought every bit "part of the criminal prosecution of a accused", described by the Latin term in personam, significant "against the person", and happens when government indicts or charges the property which is either used in connexion with a crime, or derived from a crime, that is suspected of existence committed past the defendant;[100] the seized assets are temporarily held and become authorities belongings officially subsequently an accused person has been convicted past a court of police force; if the person is found to be not guilty, the seized property must be returned.

Normally both ceremonious and criminal forfeitures require involvement by the judiciary; all the same, there is a variant of civil forfeiture called administrative forfeiture which is essentially a civil forfeiture which does not require involvement past the judiciary, which derives its powers from the Tariff Human activity of 1930, and empowers police force to seize banned imported trade, besides as things used to import or transport or store a controlled substance, coin, or other belongings which is less than $500,000 value.[100]

Run across also [edit]

- United States ramble criminal process

References [edit]

- ^ a b "James Madison'southward Proposed Amendments to the Constitution", Annals of Congress (June eight, 1789).

- ^ Obrien, David. "Fifth Amendment: Play a joke on Hunters, Old Women, Hermits, and the Burger Court", Notre Matriarch Law Review, Vol. 54, p. 30 (1978).

- ^ United states of america v. Calandra, 414 U.S. 338 (1974)

- ^ Duke 5. United States, 301 U.S. 492 (1937)

- ^ Joshua E. Kastenberg, Cause and Effect: The Origins and Affect of Justice William O. Douglas' Anti-Armed services Credo from Earth War Ii to O'Callahan v. Parker, 26 Thomas Cooley 50. Rev (2009)

- ^ Solorio v. Usa, 483 U.S. 435 (1987)

- ^ Hurtado v. California, 110 U.Southward. 517 (1884)

- ^ Ex parte Wilson, 114 U.S. 417 (1885)

- ^ U.s.a. v. Cox, 342 F.2d 167, 187 fn.7 (fifth Cir. 1965) (Wisdom, J., specially concurring) citing Greenidge, 37.

- ^ Greenidge, Abel Hendy Jones (1894). Infamia: Its Place in Roman Public and Private Law. London: Claredon Press. Retrieved 29 Baronial 2014.

- ^ Brownish, Susan. "Federal M Jury – "Infamous crimes"—part 1". University of Dayton School of Law. Archived from the original on June 21, 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ^ Harper, Timothy (October 2, 2007). The Consummate Idiot's Guide to the U.S. Constitution. Penguin Grouping. p. 109. ISBN978-1-59257-627-two.

Nonetheless, the Fifth Amendment contains several other important provisions for protecting your rights. It is the source of the double jeopardy doctrine, which prevents government from trying a person twice for the same law-breaking ...

- ^ North Carolina v. Pearce, 395 U.S. 711 (1969).

- ^ Crist v. Bretz, 437 U.S. 28 (1978).

- ^ Fong Foo v. United States, 369 U.South. 141 (1962); Sanabria v. United States, 437 U.S. 54 (1978).

- ^ United states of america five. Martin Linen Supply Co., 430 U.S. 564 (1977).

- ^ Burks v. United States, 437 U.S. 1 (1978).

- ^ Dark-green v. United States, 355 U.Southward. 184 (1957).

- ^ Ashe five. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970).

- ^ Yeager 5. United States, 557 U.S. 110 (2009).

- ^ Serfass v. United States, 420 U.S. 377 (1973).

- ^ United States v. Scott, 437 U.Southward. 82 (1978).

- ^ Wilson v. The states, 420 U.Due south. 332 (1975).

- ^ Smith 5. Massachusetts, 543 U.S. 462 (2005).

- ^ Ball v. U.s.a., 163 U.S. 662 (1896).

- ^ United states of america 5. Tateo, 377 U.Southward. 463 (1964).

- ^ Tibbs v. Florida, 457 U.S. 31 (1982).

- ^ Aleman v. Judges of the Excursion Court of Cook County, 138 F.3d 302 (seventh Cir. 1998).

- ^ Blockburger v. U.s.a., 284 U.S. 299 (1932). Run into, eastward.g., Chocolate-brown 5. Ohio, 432 U.S. 161 (1977).

- ^ Garrett five. U.s.a., 471 U.Due south. 773 (1985); Rutledge v. United States, 517 U.S. 292 (1996).

- ^ United States five. Felix, 503 U.Southward. 378 (1992).

- ^ Missouri v. Hunter, 459 U.S. 359 (1983).

- ^ Grady v. Corbin, 495 U.Southward. 508 (1990).

- ^ United States v. Dixon, 509 U.South. 688 (1993).

- ^ Oregon v. Kennedy, 456 U.South. 667 (1982).

- ^ Arizona v. Washington, 434 U.Southward. 497 (1978).

- ^ Black's Law Dictionary, p. 690 (fifth ed. 1979).

- ^ From "Cocky-Incrimination, Privilege Confronting," Barrons Law Dictionary, p. 434 (2nd ed. 1984).

- ^ Ohio five. Reiner, 532 U.S. 17 (2001), citing Hoffman v. U.S., 351 U.South. 479 (1951); cf. Counselman v. Hitchcock, 142 U.Southward. 547 (1892)

- ^ Amar, Akhil Reed (1998). The Bill of Rights. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 84. ISBN0-300-08277-0.

- ^ Amar, Akhil Reed (2005). America'south Constitution . New York: Random House. p. 329. ISBNane-4000-6262-four.

- ^ Greaves, Richard L. (1981). "Legal Problems". Society and religion in Elizabethan England. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Printing. pp. 649, 681. ISBN0-8166-1030-4. OCLC 7278140. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

This situation worsened in the 1580s and 1590s when the machinery of ... the High Commission, was turned confronting Puritans ... in which a key weapon was the adjuration ex officio mero, with its capacity for self incrimination ... Refusal to take this adjuration usually was regarded as proof of guilt.

- ^ Ohio v. Reiner, 532 U.S. 17 (2001).

- ^ 570 U.Southward. 12-246 (2013).

- ^ "A Law Professor Explains Why You Should Never Talk to Police". Vice.com. 2016.

- ^ "A 5-4 Ruling, One of Three, Limits Silence'south Protection". The New York Times. 18 June 2013.

- ^ See, e.yard., Rule 608(b), Federal Rules of Evidence, as amended through Dec. 1, 2012.

- ^ Michael J. Z. Mannheimer, "Ripeness of Self-Incrimination Clause Disputes", Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Vol. 95, No. four, p. 1261, footnote one (Northwestern Univ. School of Police force 2005), citing Malloy 5. Hogan, 378 U.South. 1 (1964)).

- ^ McCarthy v. Arndstein, 266 U.S. 34 (1924)).

- ^ 509 F. 2d 863 (2d Cir. 1975).

- ^ 132 F. Supp. 2nd 248, 251-53 (S.D.Northward.Y. 2001), aff'd, 279 F.3d 155, 162 (2d Cir. 2002), cert. denied, 537 U.S. 1028 (2002).

- ^ 134 F. Supp. 2d 90, 95 (D.D.C. 2001).

- ^ 373 U.South. 503 (1963).

- ^ a b J.D.B. 5. North Carolina, "United States Supreme Court", June sixteen, 2011, accessed June 20th, 2011.

- ^ Yarborough v. Alvarado, "The states Supreme Court", June one, 2004, accessed June 20th, 2011.

- ^ Justice Kennedy (2010-06-01). "Berghuis v. Thompkins". Constabulary.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2013-07-fourteen .

- ^ See Salinas 5. Texas, no. 12-246, U.S. Supreme Court (June 17, 2013).

- ^ Mukasey, Marc L.; Jonathan Due north. Halpern; Floren J. Taylor; Katherine One thousand. Sullivan; Bracewell & Giuliani LLP (June 21, 2013). "Salinas v. Texas: Your Silence May Exist Used Against You Re: U.South. Supreme Court Litigation". The National Law Review . Retrieved vii July 2013.

- ^ 116 U.S. 616 (1886).

- ^ U.Due south. v. Kordel, 397 U.South. 1 (1970).

- ^ Braswell v. U.Southward., 487 U.S. 99 (1988).

- ^ 380 U.South. 609 (1965)

- ^ 425 U.S. 308, 318 (1976).

- ^ Id. at 319 (quoting United states of america ex rel. Bilokumsky v. Tod, 263 U.S. 149, 153–154 (1923)).

- ^ Id. (quoting U.s. v. Hale, 422 U.S. 171, 176 (1975)).

- ^ "Boyd v. U.s. :: 116 U.Southward. 616 (1886) :: Justia U.Southward. Supreme Courtroom Middle". Justia Law.

- ^ Rotsztain, Diego A. (1996). "The 5th Amendment Privilege Against Cocky-incrimination and Fear of Strange Prosecution". Columbia Law Review. 96: 1940–1972. doi:ten.2307/1123297. JSTOR 1123297.

- ^ 274 U.Due south. 259 (1927).

- ^ U.s.a. v. Sullivan, 274 U.Southward. 259 (1927).

- ^ 424 U.S. 648 (1976).

- ^ Garner five. U.s., 424 U.S. 648 (1976).

- ^ Miniter, Frank (2011). Saving the Bill of Rights: Exposing the Left's Campaign to Destroy American Exceptionalism. Regnery Publishing. p. 204. ISBN978-one-59698-150-8.

- ^ The states v. Pilcher, 672 F.2nd 875 (11th Cir.), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 973 (1982).

- ^ United states five. Wade, 585 F.2d 573 (fifth Cir. 1978), cert. denied, 440 U.Due south. 928 (1979) (italics in original).

- ^ United States five. Johnson, 577 F.2d 1304 (5th Cir. 1978) (italics in original).

- ^ United States v. Brown, 600 F.2d 248 (10th Cir. 1979).

- ^ 406 U.Southward. 441 (1972).

- ^ 382 U.S. 70 (1965).

- ^ 395 U.S. half-dozen (1969).

- ^ 390 U.Due south. 85 (1968).

- ^ Justice Blackmun (1988-06-22). "John Doe 5. United States". Police.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2016-01-31 .

- ^ Justice Stevens (1988-06-22). "John Doe v. U.s.". Law.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2016-01-31 .

- ^ Justice Stevens (2000-06-05). "United States v. Hubbell". Law.cornell.edu . Retrieved 2016-01-31 .

- ^ In re Chiliad Jury Subpoena to Sebastien Boucher , No. two:06-mj-91, 2009 WL 424718 (D. Vt. February nineteen, 2009).

- ^ See docket entry 247, "Guild GRANTING APPLICATION UNDER THE ALL WRITS Human action REQUIRING DEFENDANT FRICOSU TO ASSIST IN THE EXECUTION OF PREVIOUSLY ISSUED SEARCH WARRANTS", United states 5. Fricosu, instance no. 10-cr-00509-REB-02, January. 23, 2012, U.S. District Court for the District of Colorado, at [one].

- ^ Jeffrey Brownish, Cybercrime Review (Jan 27, 2012). "Fifth Amendment held not violated by forced disclosure of unencrypted bulldoze". Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ In Re Grand Jury Amendment Duces Tecum Dated March 25, 2011 671 F.3d 1335 (11th Cir. 2012) (the cited reporter is wrong and leads to Minesen Co. v. McHugh , 671 F.3d 1332, 1335 (Fed. Cir. 2012).).

- ^ Jeffrey Brown, Cybercrime Review (February 25, 2012). "11th Cir. finds Fifth Amendment violation with compelled production of unencrypted files". Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved July seven, 2012.

- ^ Kravets, David (23 April 2013). "Here'due south a Skillful Reason to Encrypt Your Information". Wired. Condé Nast. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ U.South. v Jeffrey Feldman , THE DECRYPTION OF A SEIZED Information STORAGE SYSTEM (East.D. Wis. 19 April 2013).

- ^ "State Court Docket Watch: State of Oregon v. Pittman". fedsoc.org . Retrieved 2022-03-10 .

- ^ International Association of Fire Chiefs (2011). Chief Officeholder: Principles and Do. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. ISBN978-0-7637-7929-0.

- ^ Madison, P.A. (2 August 2010). "Historical Analysis of the first of the 14th Subpoena'southward Showtime Section". The Federalist Weblog. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ "The Bill of Rights: A Brief History". ACLU. Archived from the original on August 30, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Honda Motor Co. 5. Oberg, 512 U.Southward. 415 (1994), at 434". Justia US Supreme Court Center. June 24, 1994. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2020.

There is, nonetheless, a vast divergence betwixt capricious grants of liberty and capricious deprivations of liberty or property. The Due Process Clause has aught to say about the sometime, merely its whole purpose is to prevent the latter.

- ^ Timothy Stoltzfus Jost (Professor of Law at the Washington and Lee University School of Law) (January 2, 2014). "The Operation of the Affordable Intendance Act's Chance Corridor Plan, p. v and vi with reference to the United States Supreme case Lynch v. United States, 292 U.S. 571, 579 (1934)" (PDF). Business firm Commission on Oversight and Government Reform of the United States Congress. Archived from the original (PDF) on February xvi, 2020.

- ^ "Lynch v. United States, 292 U.Due south. 571 (1934)". Justia US Supreme Courtroom Center. June 4, 1934. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Come across Berman v. Parker.

- ^ Wegner five.Milwaukee Common, Urban center of Minneapolis 479 N.West.second 38 (Minn. 1991) and Steele v. City of Houston 603 S.Due west.2nd 786 (1980)

- ^ a b c d U.s.a. Section of Justice (January 2013). "Types of federal forfeiture". United States Department of Justice. Retrieved Oct 14, 2014.

... (Source: A Guide to Equitable Sharing of Federally Forfeited Property for State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, U.S. Section of Justice, March 1994)

- ^ Brenda J. Buote (January 31, 2013). "Tewksbury motel owner glad to close book on seizure threat". Boston Globe. Retrieved Oct 11, 2014.

... Cabin Caswell ... free from the threat of seizure past US Chaser Carmen Ortiz ...

- ^ a b John Burnett (June xvi, 2008). "Seized Drug Assets Pad Police Budgets". NPR. Retrieved Oct eleven, 2014.

... Every year, about $12 billion in drug profits returns to Mexico from the globe's largest narcotics market—the United States. ...

- ^ Craig Gaumer; Assistant United States Attorney; Southern District of Iowa (Nov 2007). "A Prosecutor's Cloak-and-dagger Weapon: Federal Civil Forfeiture Law" (PDF). United states Department of Justice. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

Nov 2007 Volume 55 Number 6 '... I of the principal advantages of ceremonious forfeiture is that it has less stringent standards for obtaining a seizure warrant ...' see pages 60, 71...

- ^ Note: the legal tests used to justify civil forfeiture vary according to state law, but in most cases the tests are looser than in criminal trials where the "beyond a reasonable doubt" test is predominant

- ^ John R. Emshwiller; Gary Fields (August 22, 2011). "Federal Asset Seizures Ascent, Netting Innocent With Guilty". Wall Street Periodical. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

... New York man of affairs James Lieto ... Federal agents seized $392,000 of his cash anyway. ...

Further reading [edit]

- Amar, Akhil Reed; Lettow, Renée B. (1995). "Fifth Amendment First Principles: The Self-Incrimination Clause". Michigan Constabulary Review. The Michigan Law Review Clan. 93 (5): 857–928. doi:10.2307/1289986. JSTOR 1289986.

- Davies, Thomas Y. (2003). "Farther and Farther From the Original Fifth Subpoena" (PDF). Tennessee Police Review (70): 987–1045. Retrieved 2010-04-06 .

- 5th Subpoena with Annotations

- "Fifth Amendment Rights of a Resident Alien Later on Balsys". Lloyd, Sean One thousand. In: Tulsa Periodical of Comparative & International Police force, Vol. half-dozen, Result ii (Spring 1999), pp. 163–194.

- "An assay of American Fifth Subpoena jurisprudence and its relevance to the S African right to silence". Theophilopoulos C. In: Southward African Constabulary Journal, Mar 2006, Vol. 123, Issue 3, pp. 516–538. Juta Law Publishing, 2006.

- "Fifth Subpoena: Rights of Detainees". The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 70(4):482–489; Williams & Wilkins Company, 1979.

- "FBAR Reporting and the Required Records Doctrine: Continued Erosion of Fifth Amendment Rights". COMISKY, IAN M.; LEE, MATTHEW D. Journal of Revenue enhancement & Regulation of Financial Institutions. Mar/Apr 2012, Vol. 25 Issue iv, pp. 17–22.

- "5th Amendment Rights of a Client regarding Documents Held by His Chaser: United States 5. White ". In: Duke Law Journal. 1973(5):1080–1097; Knuckles University School of Law, 1973.

- Matthew J. Weber. "Warning—Weak Countersign: The Courts' Indecipherable Approach to Encryption and the Fifth Amendment", U. Ill. J.Fifty Tech & Political leader'y (2016).

External links [edit]

- Cornell Constabulary Information

- 1954 essay on reasons to plead the 5th

- Don't Talk to the Police Video

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fifth_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution

0 Response to "what amendment is the right to know the witnesses against oneself"

Post a Comment